Monitoring of Standalone Equipment’s General Alarms

Miles Ryan, P.E., writes a monthly column in Engineered Systems Magazine on Building Commissioning. Read July’s column below:

It is very common for designers to specify the building automation system (BAS) monitor the general alarm produced by standalone equipment. Standalone equipment is equipment that operates off its own controls, rather than have the BAS dictate how and when all of the internal components are to operate. It is commonly said that such standalone equipment has self-contained controls, or has an onboard controller. Several examples of standalone equipment from some of my recent projects are listed below, but really the possibilities are limitless.

- Glycol fill stations

- Sump pumps

- Booster pumps

- Water softeners

- UV lights located downstream of AHU cooling coils

- Humidifiers

- Domestic hot water master mixing valves

- Water heaters

- Snowmelt systems

- Medical air compressors

- Medical vacuum pumps

- Roof leak detection systems

- Variable frequency drives

- Pure water skids

- Boilers*

- Chillers*

* Though it is common for a BAS to enable this equipment and write it a setpoint, the internal components of the equipment are controlled by the onboard controller which is capable of detecting alarm conditions with its onboard instrumentation.

Reasons for General Alarm Monitoring

Standalone equipment has controllers and associated instrumentation that can be factory programmed to identify when the equipment is not operating as it should. The level of sophistication that can be implemented to identify such alarm conditions is much higher when devised by the manufacturers of the equipment, those who know the equipment best. Additionally, those alarm algorithms can be checked out in a factory prior to the equipment arriving to site.

Often these onboard controllers have local display panels which will allow for local visual, and possibly audible alarms to be generated. Such equipment may be in a space that is often unoccupied, or not occupied by personnel (e.g. facility operations staff) who would actually pay attention to an alarm.

A BAS has the functionality of sending notifications to facility staff via text, page, email or displayed on the graphical user interface when alarms are generated. This is a capability most standalone equipment would not have, or at least it would not be economical to implement.

As such, it is common for the designer to want to combine the enhanced alarm detection capabilities of the onboard controller with the enhanced notification capability of the BAS. The hard part is getting the BAS to know when an alarm condition exists worth notifying folks of.

How General Monitoring Is Performed

The most cost effective, and reliable solution is for the standalone equipment’s onboard controller to broadcast an alarm by use of an alarm contact. The BAS can then have a set of wires running from a BAS controller to the standalone equipment’s onboard controller. Common specification language for this arrangement would be:

- “The BAS is to monitor the dry alarm contact from the ________’s control panel. The BAS shall generate an alarm and send a notification when the control panel indicates an alarm condition.”

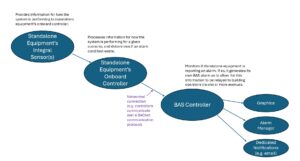

Figure 1 below shows how alarm conditions are detected, and the information relayed to facility operations when using a hardwired connection.

Figure 1: Information flow for hardwired general alarms.

A second common approach is for the standalone equipment’s onboard controller to be brought onto the BAS network. If such a network connection is performed, then the BAS usually has access to a lot more information about the operation of the equipment than just a general alarm condition. The struggle here is for the temperature controls contractor installing the BAS to sift through all the available information to ensure they are monitoring the correct items. Common specification language for this arrangement would be:

- “The BAS shall communicate with the ________ via a networked connection. The BAS shall indicate an alarm when the control panel indicates an alarm condition. Coordinate with the owner on which points of information are to be displayed on the BAS graphic.”

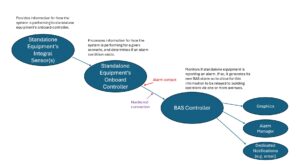

Figure 2 below shows how alarm conditions are detected, and the information relayed to facility operations through a networked connection.

Figure 2: Information flow for network-monitored general alarms.

What Can Go Wrong?

Ensuring a general alarm is correctly monitored by the BAS, and the BAS in turn generates its own alarm and associated notification(s) may sound like the easiest functional test a commissioning provider could perform. I certainly once believed that to be true. But having gone through this process a lot, I would estimate over 70% of the time this short test procedure fails. So, what goes wrong?

For a hardwired connection (reference Figure 1), issues can occur in each step of the information flow. Here are some of the items I have seen.

- Standalone equipment’s integral sensors don’t work.

- For example, a failed pressure switch on a medical air compressor.

- Just ask any large mechanical contractor how often the equipment shows up with failed components. The rate is staggering.

- The standalone equipment’s onboard controller doesn’t generate an alarm even when its sensors are providing the combination of readings which warrant one.

- For example, an incorrect alarm threshold is being used.

- The standalone equipment’s onboard controller generates a local alarm (visual and/or audible) as it should, but the controller wasn’t configured during startup to trigger its alarm contact which is being monitored by the BAS.

- On a recent project, the equipment rep who performed startup “wasn’t aware the BAS was planning to monitor the contact” despite it being clearly identified in the equipment’s specification, in the equipment schedule on the mechanical drawings and in the temperature controls diagrams/specifications.

- The alarm contact on the standalone equipment’s onboard controller doesn’t even exist.

- This could be an oversight from the equipment vendor, or it may be the equipment specification never required it, and such a need for an alarm contact was only referenced in the temperature controls specification.

- The BAS contractor lands their wires on the incorrect contact.

- This could be a lack of attention to detail on the part of the BAS contractor’s installing electrician.

- This could also be attributed to the standalone equipment’s submittal having an incorrect wiring diagram. It is alarming (no pun intended) how often that is the case.

- Compromised wiring between the standalone equipment’s onboard controller and the BAS controller.

- The BAS controller is not programmed to generate its own alarm when it sees the standalone equipment in alarm.

- The BAS controller may generate an alarm, but then not properly relay that information to one or all of the three common areas where that information is sent (graphics display, alarm manager and dedicated notifications to facility staff).

Network connections (reference Figure 2) see many of the issues listed above. Additionally, getting the BAS to know exactly which information is the “general alarm” is often not easy.

- There are often endless amounts of alarm points and the question becomes “what does the owner really want to alarm on the BAS?” My advice, keep it to a minimum.

- The points list from the manufacturer of the standalone equipment is often hard to track down or an incorrect points list is provided to the BAS contractor.

- The points list contains such a convoluted naming convention that even the multilingual BAS technicians with PhDs leave the jobsite in tears.

As you can see, there are many things that can go wrong. I have personally seen every one of the issues listed above, some of them many times. When issues are encountered during functional testing, the amount of coordination needed to rectify the issue is extensive. A simple test that a commissioning provider budgeted maybe 20 minutes for turns into the hardest action item for the construction team to bring to the finish line.

Recommendations

Since this general alarm monitoring can get so painful, let’s avoid it if we can. I have seen owners witness the construction team fumble through this general alarm monitoring for weeks before they say “do we really even need this? The shift supervisor’s desk is 5 feet from that sump pump, certainly they are going to know if it is in alarm.” So, I encourage commissioning providers to question the owner early on if such alarm monitoring is truly warranted.

If it is needed, here are a couple things commissioning providers can do to improve the chances of this actually working:

- Ensure the standalone equipment’s specification and equipment schedule in the design drawings both make references to the required level of BAS interface (hardwired or network). Having it in two locations decreases the chances of this being missed.

- Ensure temperature controls drawings and specifications clearly call for the required level of interface to the standalone equipment’s onboard controller. And make sure that matches what is being specified for the standalone equipment itself!

- Encourage the design team to engage the vendor on what scenarios constitute a general alarm to be broadcasted, rather than specifying alarm conditions that may not be possible for the nonprogrammable onboard controllers to identify.

- Push for wiring diagrams and/or points list to be provided in the equipment’s submittal.

- Clearly establish expectations with owners, contractors and their vendors for what your test will include and who will need to be onsite to assist.

- Require contractor pretesting as part of your prerequisites for testing,

- When it comes to testing, go as far upstream as possible. Merely overriding an input on the BAS controller is not testing anything upstream. Any issues with the standalone equipment’s integral sensor(s), standalone equipment’s onboard controller’s alarm logic, or communication (hardwired or networked) between the two controllers would not be identified.

- For projects of extended duration, there is a chance the standalone equipment went into alarm on its own sometime during the construction phase. Review alarm logs at the equipment local control panel, then see if the BAS correctly observed that alarm and generated its own alarm at the same time. This approach may save you having to try and force an alarm condition yourself.